DISCLAIMER: I’m in my 50’s, I’m a dad, a CEO, and a nerd. I have a Ph. D. in applied behavior analysis, and I’m fascinated by the inner working of our minds. My writing will be sprinkled with geek references, dad jokes, phrases that were barely cool when introduced 10 to 20 years ago, brain science bits, and CEO business babble.

The 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle, posits that 80% of results come from 20% of causes (Thanks ChatGPT! Have you been working out? You look great! —call back to the first blog article).

In terms of employees, the 80/20 rule has been used to claim that 20% of staff generate 80% of the best work in an organization and that 80% of problems are caused by 20% of staff who don’t pull their weight or actively work against organizational objectives.

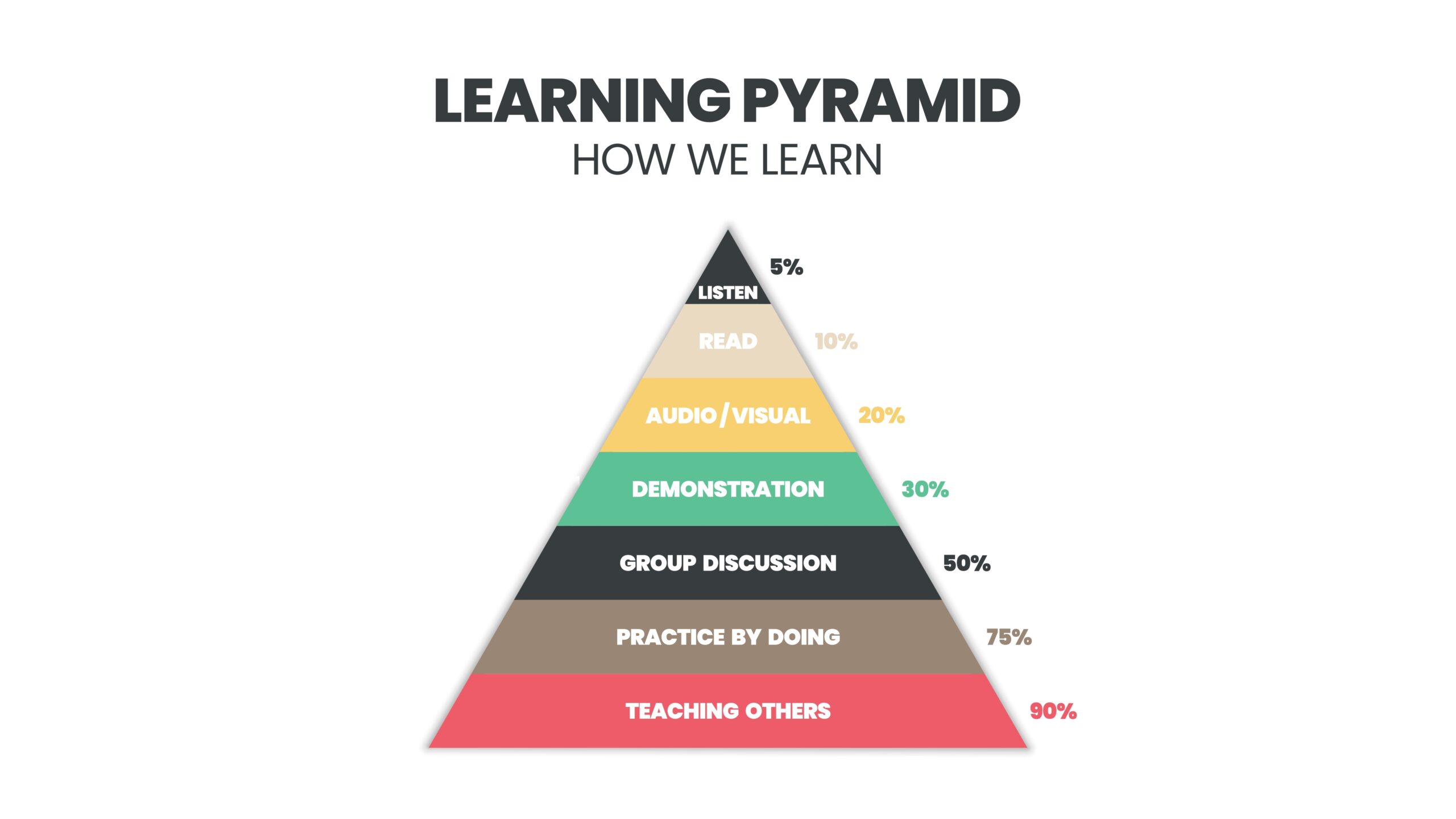

I used to teach an experimental design class to graduate students in an ABA program. When we got to statistical analysis, I gave my students a warning—never trust perfect percentages. My go-to example was the “Learning Pyramid.”

I’ve seen this pyramid, that describes average learning retention rates based on learning style, in textbooks, research papers, countless articles, and blogs. It’s Bull fill in the blank with your preferred excrement synonym. Look at those percentages. Can they be any more perfect? Here’s a challenge. I’ve got a crisp $100 bill for the first person to email me the citation for the original research paper that details the experiment that generated these results (jpingo@nullgoldiefloberg.org). Hint: I’d suggest checking the warehouse where they stored the Ark of the Covenant and the Roswell aliens.

I get that the 80/20 rule is not meant to be a hard empirical measure, but these types of perfect percentages can cause lazy thinking. We can lean on these business tropes instead of asking the hard questions. What is our percentage of staff who are pulling their weight (or more)? I bet it’s not a perfect 20%. Going deeper, how do we determine who these extremely valuable staff are?

We asked ourselves this question and came up with two answers. Our most valuable people, are those who do two things consistently:

- They Show Up.

- They Do Good.

Wow John. That’s deep. I know. Not rocket surgery. But simple does not mean wrong. A good performance metric needs to be important to the organization and easy to measure. Let’s first look at Showing Up.

Is showing up important? Think about the ripple effect that staff calling off shifts or showing up late has on people in our organizations. Think about the anxiety and frustration it generates and how corrosive that is on the quality of life of the people we serve and our staff. I can’t imagine how the people we serve must feel when staff they depend on don’t show up. I was a DSP (Direct Support Professional). I remember how it felt after a long shift to be looking at the clock as my shift end time arrived, but my relief was a no show. Each minute stretched on like an hour and frustration built as I felt taken advantage of.

Is showing up an area where we can improve? From May 2022 to June 2023, we averaged 29 absences per week, Monday through Friday. The average was 16 absences for weekends for the same time period. If each of those absences represented a single 8-hour shift (some are inevitably longer shifts, but let’s keep it simple), we’re looking at 232 hours to cover during the week and 128 hours during the weekend, for a total of 360 hours. That’s equivalent to 9 FTE DSPs per week. Does anyone have an extra 9 staff hanging out, waiting to jump in and fill schedule holes? I didn’t think so. So yes, there is room for improvement.

What about ease of measurement? We have a point-based attendance system. We define showing up as having 6 or less attendance points per quarter. That is the equivalent of 2 absences per quarter. If a staff member is absent for several days due to an illness, illness of a child, etc., that only counts as 1 absence in terms of points. We track the points already so it’s an easy metric to watch.

Doing Good is a little trickier. We can all agree that a big part of doing good in an organization is correctly implementing job responsibilities. How do you measure it? We assumed that staff are doing good unless we discovered a discrepancy between desired performance and observed performance. When a performance discrepancy is found, we address it with our progressive coaching system. The system has multiple levels, with the first being informal coaching. We decided to define doing good as needing no more than informal coaching in any specific area of performance. Again, we already track coaching activity so we’re good there.

Now that we can identify our most valuable staff, how many full-time DSPs meet the metrics of Showing Up and Doing Good? Six DSPs or about 16% of our full-time team who had been with us long enough to qualify. The low number could be disheartening but it can also be seen as an opportunity. A big pool of talent waiting to be tapped. Or maybe it’s a keg of talent. You don’t tap a pool. So, what are we doing to tap that talent keg?

Tune in next week for…There’s Gold in them thar organizations!